We named our project Horizons. Our word choice alludes both to the literal horizon of Bamiyan whose majestic view sculpted our architectural proposal into being; and also the new horizons awaiting Afghanistan, as it faces a hopeful future after decades of instability and strife. If the history, culture and social resilience of Bamiyan are going to shine, it will be through its people. We want to create architecture precisely for them.

Community

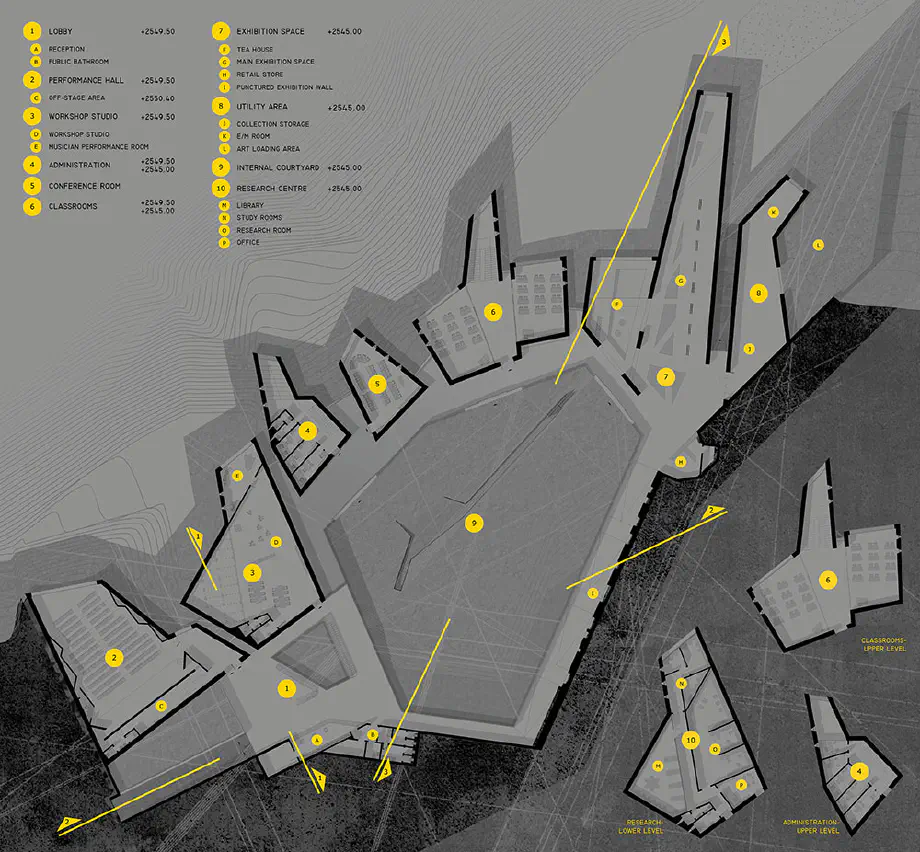

On designing our entry, the first question we had to answer was: what will the role of the Cultural Centre be for the people living in Bamiyan? Our vision was that of a living space, that would turn into a hub of activity throughout the day and the year. The programmatic requirements already provide us with the map of the basic communal activities fostered: seminar rooms and workshops, a library, a museum as well as a multifunctional hall. It is however, the spaces that are not described in the program that are key to the social activation of architecture.

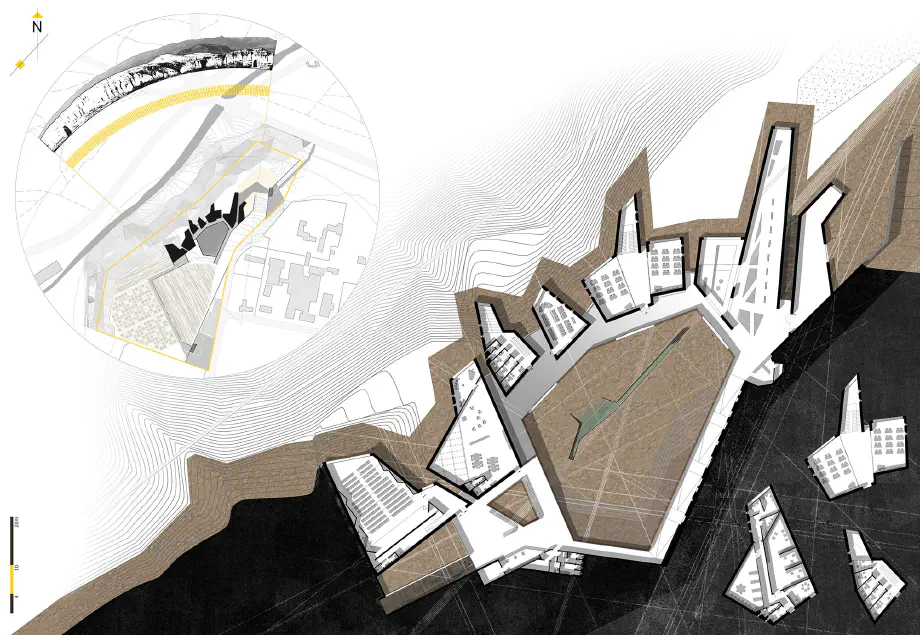

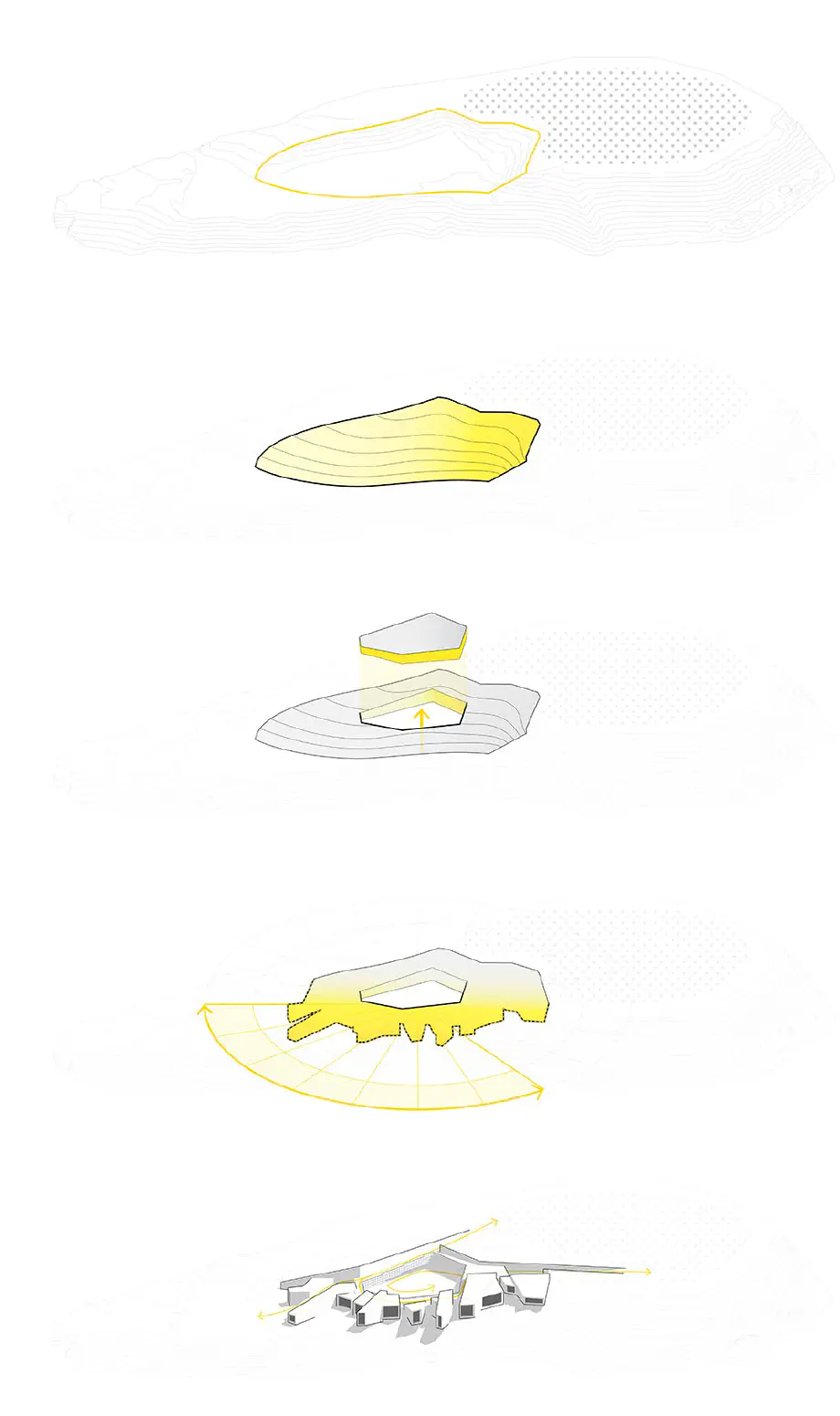

We started by refilling the landscape of the quarried hill, to create a more natural topography that blends into its surroundings; out of our artificial hill, we excavated a court. Following seasonal variation, everything happens around and inside the court, which is the beating heart of our cultural centre: open-air seminars, flea markets, citizens’ gatherings, movie screenings, theatre shows and rallies. The variety of activities is only limited by the needs and ambitions of the Bamiyan people.

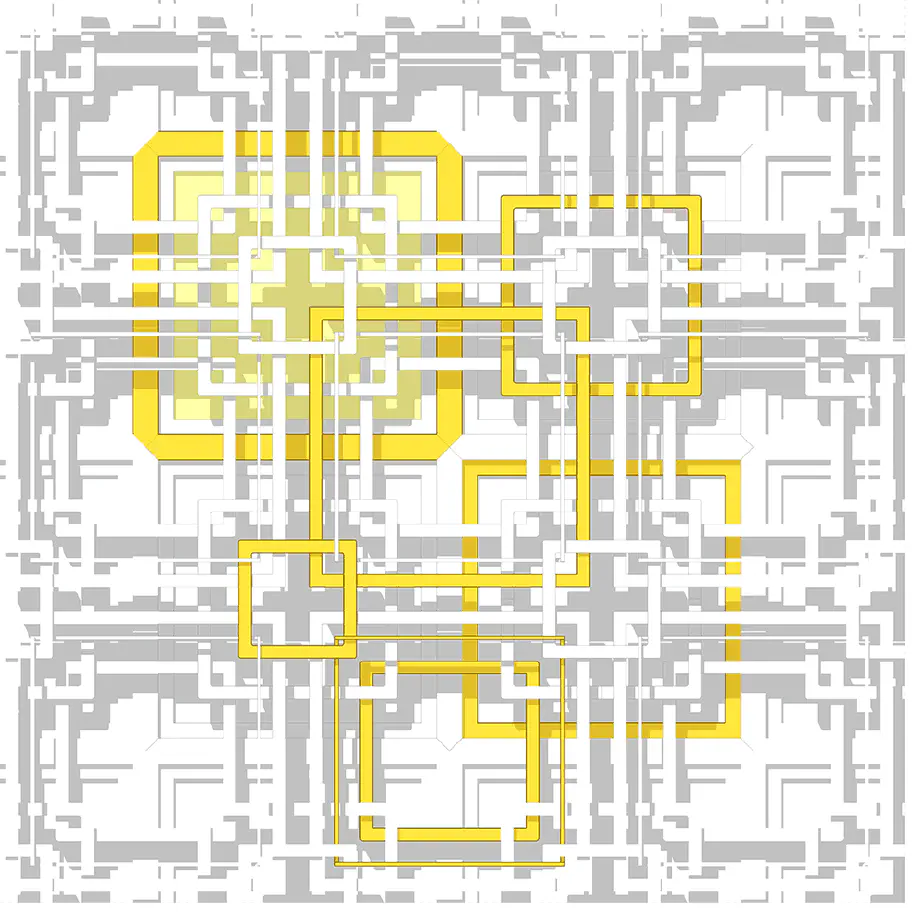

The proposed learning spaces are arranged around the court, while the in-between space is a sheltered arcade that acts as a filter between the buildings and the courtyard. This arrangement dates centuries back to the original typologies of public architecture for a variety of people: from Afghans and Persians to the Greeks. Since Bamiyan is unique in being the meeting place between these cultures, we believe that employing an archetypical form would create a timeless architecture, whose main component is social, not material.

Heritage

Bamiyan’s rich history is not only documented in archives; it is a living reality, revealed by surviving monuments like the majestic Buddha sculpture cliffs. The main component of the program addressing Bamiyan’s heritage is, of course, the museum. Our intention was, however, that the whole cultural complex enhances the experience of the place and evokes its special history. When one approaches the building complex, the view to the cliffs is unhindered and open; the volumes being gently sunken below eye level and barely implied as forms in the landscape. As visitors descend towards the courtyard, they perceive that not only the buildings themselves, but also the gaps between the volumes frame views to the surrounding heritage sites. These niches form small resting spaces for discussion and contemplation.

Descending the ramped arcade towards the museum, the right hand wall is punctured with niches featuring exhibits with a more public character; one can enjoy them without entering the museum. Finally, the culmination of the arcades and the courtyard is the museum: an elongated volume that is organized as a narrative journey, at the end of which lies the culminating panorama of the Bamiyan Buddhas.

Traces of historical heritage resonate throughout the whole complex. In turn, through careful geometrical and material treatment, architecture blends itself into the landscape, while at the same time maintaining a particular and contemporary character.

Sustainability

When designing in an area without stable access to power and water, we bear the responsibility of creating an architecture that will be resilient and adaptable, able to function without amenities that in contemporary urban societies are a given.

In complete agreement with the brief, we also felt that not only local materials but also local building technologies have to be employed, for a two-fold benefit. Firstly, the construction of the project will offer employment to local builders and artisans, without relying heavily to external know-how. Secondly, after the completion of the Bamiyan cultural centre, it is of utmost importance to ensure that the community of local citizens can take it upon themselves to take care of and sustain the building. A culture of sharing responsibility and working towards communal goals already exists in Bamiyan; this is an important asset that we want to use as a design parameter. Therefore, the main building material is adobe, with concrete only used for floor slabs and foundations. The internal courtyard is surrounded by a wooden mashrabiya of varying thickness and depth, which also includes the windows and panels that shield the arcade from adverse weather conditions. The structure is very simple despite its apparent complexity: basically comprised of wooden square frames, assembled on top of each other. It is easy to disassemble and repair damaged parts individually. It is not only the materials that address question of sustainability though, but also the design itself. The larger glazed openings of the adobe volumes receive plenty indirect northern light, while the southern openings offer filtered sunlight through the mashrabiyas. The thickness of the walls provide the building with heat mass, which means that it is easier to keep cool during the summer and warm during the winter, forfeiting the need for insulation. The whole complex lies below the road-level on top of the hill, therefore facilitating the circulation of water from higher wells. Consequently, we propose collecting some of the water in a small cooling pool in the middle of the court, which faces in the direction of Mecca and provides with a visual queue for prayer. The pool is shallow and can be emptied in a matter of minutes, when the entire space is used for activities.